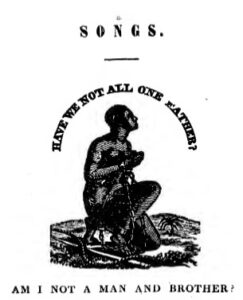

The movement to abolish slavery in the US gave rise to a wealth of songs to support the cause. As with songs for women’s suffrage and those of other social movements, new lyrics were often set to familiar tunes. A number of songsters were created to share them. Some lyrics appeared in abolitionist periodicals, and sheet music was also published.

My engagement with this music began with a gig at local western Maine historical landmark Parsonsfield Seminary and my desire to highlight its role as a way station on the Underground Railroad. My research into these songs continues. Though I have much more to learn, I’d like to share what I’ve found thus far, prioritizing Black voices first and including links to primary sources whenever possible:

William Wells Brown escaped slavery himself and went on to become a conductor on the Underground Railroad and a noted writer and antislavery lecturer on both sides of the Atlantic. He moved to England for a time to avoid re-enslavement, living there until a friend bought his freedom. He compiled three editions of The Anti-Slavery Harp: A Collection of Songs for Anti-Slavery Meetings. All are available for free download: 1848, 1849, and 1851.

Freeborn in Ohio, Black abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor Joshua McCarter Simpson was a prolific writer of anti-slavery lyrics. As he said in his 1854 collection The Emancipation Car, Being an Original Composition Of Anti-Slavery Ballads, Composed Exclusively For the Under Ground Rail Road (reprinted 1874), “As soon as I could write, which was not until I was past twenty-one years old, a spirit of poetry, (which was always in me,) became revived, and seemed to waft before my mind horrid pictures of the condition of my people, and something seemed to say, ‘Write and sing about it—you can sing what would be death to speak.’ So I began to write and sing.” He also produced the 1852 collection Original Anti-Slavery Songs and a number of broadsides, downloadable here.

Henry “Box” Brown escaped slavery by having himself secretly shipped from Richmond, VA to Philadelphia in a box 3′ long, 2 1/2′ deep, & 2′ wide. The trip took 27 hours. He lived to tell about it as an anti-slavery lecturer, and to sing about it as a travelling performer. He published broadsides in the US of lyrics recounting his Escape from Slavery, set to the Stephen Foster tune Uncle Ned, and his Hymn of Thansgiving upon release from the box, set to a church tune. He also released an edition of Escape from Slavery in England after moving there following passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which made it dangerous for him to remain in the US.

Formerly enslaved, evangelist and advocate for African-Americans‘ and women’s rights Sojourner Truth was known for her compelling voice both as an orator and as a vocalist. There is an account of her quelling a violent mob with her singing. She wrote the lyrics I Am Pleading for my People (see p. 302-304 of her Narrative of Sojourner Truth), reportedly sung to the tune of Auld Lang Syne. She was also associated with a song celebrating Black soldiers in the Union Army. Her version, The Valiant Soldiers, seems to be based on The Marching Song of the First Arkansas Colored Regiment (more info here; register to view), attributed to that regiment’s White captain, Lindsay Miller. He may have compiled it from the singing of men under his command. Both versions were sung to the tune of John Brown’s Body/Battle Hymn of the Republic.

More Black voices are amplified by the Songs of Slavery and Emancipation project, which “presents recently discovered songs composed by enslaved people and explicitly calling for resistance to slavery. Some originate as early as 1800 and others as late as the outbreak of the Civil War. The project also includes long-lost songs of the abolitionist movement, some of which were written by fugitive slaves as well as free black people, challenging common misconceptions of abolitionism.” Initiated by Matt Callahan of Art and History in Politics, the project encompasses a double CD, a book, and a documentary film.

The Hutchinson Family Singers were New Hampshire natives who sang for abolition, women’s rights, temperance, and other causes, as well as dramatic, humorous, and sentimental pieces. They toured extensively in the US and Britain, often with their friend Frederick Douglass. John Hutchinson described their career in Story of the Hutchinsons, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (1896). Abolitionist lyrics are included in The Hutchinson Family’s Book of Words (1853), Book of Poetry of the Hutchinson Family (1858), Hutchinson’s Republican Songster for 1860, and The Book of Brothers (1864). Sheet music of some of their anti-slavery songs are online: Right Over Wrong, Slavery Is a Hard Foe to Battle, Little Topsy’s Song, and The Ghost of Uncle Tom (the last two based on Uncle Tom’s Cabin). Their Get Off the Track! was written for the tune to Old Dan Tucker, turning that blackface minstrel show hit to a very different purpose. Some modern recordings of their repertoire are described here (scroll down). Search for their name on YouTube for more.

Massachusetts-based singer Deborah Anne Goss performs in character as Abby Hutchinson Patton, one of the Hutchinson Family Singers. Her contact info is in her New Hampshire Humanities profile. Deborah has recorded an a capella collection of Songs of the Abolitionists, available here in mp3 format, with album notes here. For a physical CD with notes for $20 postpaid, contact Deborah at brightlook16 (at) hotmail.com.

New Hampshire-based singer Steve Blunt also performs in character as one of the Hutchinson Family Singers, in his case as John Hutchinson. His contact info is in his New Hampshire Humanities profile.

The Dutchess Antislavery Singers, based in New York state and affiliated with the Mid-Hudson Antislavery History Project, also present abolitionist songs in period costume. Their book 36 Antislavery Songs includes music as well as words. Their webpage links to videos of a number of the songs (scroll down). See also their extensive materials on using music to teach abolitionist history in middle and high schools. FMI: palexb711 (at) gmail.com or MHAHP, P.O. Box 3647, Poughkeepsie, NY 12603

American Antislavery Songs: A Collection and Analysis by Vicki L. Eaklor (Greenwood Press, 1988) is a major resource. As the publisher’s website says, “This comprehensive collection of 492 songs … is the only collection of antislavery songs currently in print [sic – see 36 Slavery Songs]. The songs are organized in six sections representing variations of antislavery thought and activity….[T]he book follows a chronology that is historically meaningful. There is an explanatory introduction for each section, in which both the music and the lyrics are discussed…. The author’s extensive introductory essay examines the historical background of the antislavery movement and its music.” The price tag is steep; you might try interlibrary loan through your local library, as I did, or borrow a digital copy here. Digital copies are available of some of the songbooks surveyed. The next eight (bulleted) items are such primary sources, listed chronologically (excluding those from William Wells Brown and Joshua McCarter Simpson above).

- Songs of the Free, and Hymns of Christian Freedom (1836) was compiled by the indomitable Maria Weston Chapman, a founder of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. Faced with an angry pro-slavery mob, she once said, “If this is the last bulwark of freedom, we may as well die here as anywhere.” Her book has lyrics only, with no tunes, though meters are noted in the index.

- Freedom’s Lyre: or, Psalms, Hymns, and Sacred Songs, for the Slave and his Friends (1840) was compiled by hymn writer and minister Edwin F. Hatfield “at the request of the Executive Committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society“. It contains lyrics only, though the meter of each piece is noted, as was common in hymnals of the time, allowing for a choice of tunes.

- The Anti-slavery Picknick: A Collection of Speeches, Poems, Dialogues and Songs; Intended for Use in Schools and Anti-Slavery Meetings (1842) was compiled by John A. Collins of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. The songs are arranged in vocal parts. According to the preface of Anti-Slavery Melodies: for the Friends of Freedom, published the following year, this book “was published… for the 1st. of August”, a day much celebrated by abolitionists (sometimes instead of the 4th of July) to mark the 1834 passage of Britian’s Slavery Abolition Act.

- Anti-Slavery Melodies: for the Friends of Freedom (1843) was prepared by Jairus Lincoln for the Hingham (MA) Anti-Slavery Society. Citing the use of music in the temperance movement, he wrote, “Let our Anti-Slavery friends turn their attention to this subject, and organize in every town an Anti-Slavery Choir.” To that end, these songs are presented in three-part harmony. The year after this book came out, Hingham hosted up to 10,000 people at the Great Abolitionist Picnic of 1844 commemorating the August 1, 1834 end of slavery in the British colonies. According to this video, compiler Jairus Lincoln was the grand marshall. Music, including a Hutchinson Family Singers performance and songs from this book, featured prominently in the event. A website “exploring the archives of the Hingham Historical Society“ has more information about this songster.

- The Liberty Minstrel, compiled by George W. Clark, went through seven editions, several of which are available online: 1844, 1845, 1846 (6th edition). Songs are arranged in vocal parts, with much of the music attributed to Clark. It served as a major source for the next item in this list.

- A Collection of Miscellaneous Songs, from the Liberty Minstrel, and Mason’s Juvenile Harp; for the Use of the Cincinnati High School (1845) was compiled and published by principal Hiram S. Gilmore, a preacher who founded the school for African-American students otherwise denied education. According to J.B. Shotwell’s A History of the Schools of Cincinnati (pp. 453-455), “Regularly during vacation the classes, under direction of the principal, journeyed through Ohio, New York, and Canada, giving concerts…, the profits of which were devoted to furnishing clothing and books and otherwise assisting indigent students.” This songster has lyrics only, though in many cases the airs are identified.

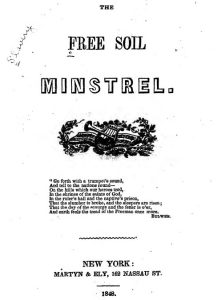

- The preface of The Free Soil Minstrel (1848) describes it as “a volume of Songs specially adapted to the glorious Free Soil movement”, which opposed the expansion of slavery into the western US territories. This book was compiled by George W. Clark, “the well-known liberty singer, whose thrilling tones have so often electrified the hearts of thousands throughout the land.” The music, much of it composed or arranged by Clark, is presented in vocal parts.

- The Harp of Freedom (1856) was also compiled by the prolific George W. Clark (see The Liberty Minstrel and The Free Soil Minstrel above). Again, the songs are arranged in vocal parts, with much of the music composed or arranged by Clark.

Song collections not mentioned as sources in Vicki L. Eaklor’s American Antislavery Songs: A Collection and Analysis include:

- A Selection of Anti-Slavery Hymns, for the Use of the Friends of Emancipation (1834), compiled by William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of The Liberator. In the preface, he said, “As the last Monday evening of the month is now extensively observed as a CONCERT OF PRAYER for the emancipation of the slaves, and the redemption of our land, this little book […] will be found useful on every such occasion.” The 32 songs are not notated, but in most cases compatible hymn tunes are suggested.

- Anti-Slavery Hymns, Designed to Aid the Cause of Human Rights (1844), compiled by George W. Stacy and further subtitled “containing original hymns written by Abby H. Price and others of the Hopedale Community, with a choice selection from other authors.” Hopedale, near Worcester, MA, was an intentional community based on pacifist, socialist, abolitionist, and egalitarian principles, understood by its members as “Practical Christianity”. This songster has lyrics only, with names of tunes given.

This list is nowhere near comprehensive. I intend to expand on it in the future, adding more sheet music and other resources. For now, I hope you will find it a useful if humble beginning. If you’d like to send corrections, suggestions, or additions, or if you’d like to explore the possibility of me bringing some of this music to your group, please be in touch. Some would prefer to sweep the difficult parts of our history and their legacy under the rug. May keeping these songs alive be a small step in another direction!